A Tribute to Preacher Jack |

| Back

to the Books and Other Writing page Back to the Archive Contents page The first time I walked in -- it was the first or second week he was there -- he was in the middle of a Little Richard medley that lasted ten or fifteen minutes, and came out of it into a sermon on the crucifixion. I don't remember how it started, but by the end he was pinned to the mirrored wall behind the piano, a crazed look in his eyes, shouting, "With nails! Nails through his hands!" Then, looking back at his right hand, his face twisted in a grimace, growling: "You want to talk about pain?" I had never seen anything like it, and for the next few years I was there almost every week. There were a few of us who were regular: Peter Levine and his lady Pam, Gary Cherone, Al Cocorochio, and a half-dozen others, plus whoever happened in that night. The music was terrific, and the sermons were astonishing. Jack understood that we weren't all Christians, and that some people were amused rather than moved. He meant it all, but he knew it worked on many levels. And his mind was amazing. Week after week, he would come up with lines that were dazzling, funny, cinematic... I persuaded someone from the National Folklife Festival to come see him, and one of that night's sermons ended with Jack on his feet, all six feet three inches of him, preaching about the coming apocalypse: "There won't be any more Penthouse magazine! It will be Repenthouse! With a centerfold of Billy Graham--" he became Graham, leveling a righteous finger at the sinners gathered before him -- "saying 'Put your clothes back on!'" Another night I brought Paul Geremia, a fine acoustic blues player and firm unbeliever. He enjoyed the music, but when Jack went into a sermon about Jesus returning to save us, Paul growled, "If he did, they'd just crucify him again." "No!" Jack shouted, fixing Paul with a ferocious look: "You can't double-cross the Christ!" I don't think I've ever seen Paul happier. Another night there was a guy in a suit sitting at the bar, just to Jack's right. He was being patronizing, requesting familiar oldies and making wise-ass remarks about Jack's sermons. Jack ignored the guy for a while, then did something I never saw before or since: he quietly began talking about how ordinary he was: "I'm just a piano player, I'm not some big, important person, like a lawyer or an insurance salesman..." I was watching him, fascinated at the change in his demeanor, and when I looked to see how the guy was taking it, the guy had vanished. I hadn't seen him leave, and he would have had to walk past me to reach the door. He simply disappeared. I had a tough couple of years in there, with a bad break-up, and those nights with Jack were my weekly church. I wasn't the only one, by a long shot -- one of his regular lines was, "I'm up here having your nervous breakdown for you." And he was. Tearing himself apart and bringing us all together.

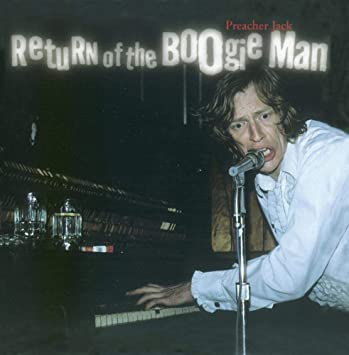

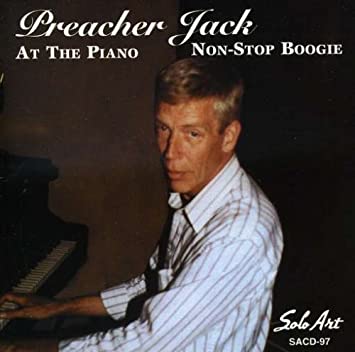

I wrote a bit as well: first a piece for the Boston Globe, which was the scaffold for what follows, then liner notes to a couple of his CDs--Jake Guralnick and I co-produced a compilation from his fine sessions for Rounder Records called Return of the Boogie Man (he had mixed feelings about that title, because he thought it made him sound evil, but acceded when I said it was my idea), and I also did notes for his Non-Stop Boogie instrumental album. What more can I say? I owe him far more than I can repay, but he liked the original version of this piece and I'm glad to have expanded it a little and to put it out there. Check out his recordings; they won't give you more than a hint of what he could do live, but even that hint is pretty amazing. Meanwhile, here's my impression of one evening's conversation with the Preacher: What would you do if you walked into a nondescript restaurant-bar in Cambridge and found yourself confronted with one of the great, wild masters of rock ’n’ roll? Would you fall on your knees and give thanks? Would you make a pilgrimage every week to relive the miracle? If so, get your knee pads ready, because Preacher Jack is back in town. From about nine o’clock till somewhere near one every Thursday night, the sanctified monster of rock and boogie woogie is having church at Frank’s Steak House, 2310 Mass. Ave., a few blocks out of Porter Square. For those who have never seen him and missed his two albums on Rounder Records in the early 1980s, the Preacher is a piano-pounding rocker who can range from classically pristine boogie-woogie to whiskey-soaked honky-tonk to incandescent gospel. The music is broken up by monologues that get weirder as the evening wears on, muttered and shouted sermons on everything from show business to politics to eternal salvation.

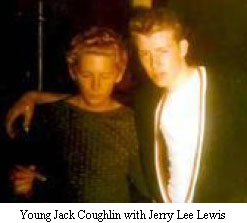

The Preacher knows it, too. “I think with my flamboyant personality, when it’s on fire, I can be dangerous enough to put that edge back into the music,” he says, as he sips a beer at one of Frank’s back tables. “It’s like Jerry Lee; he’s even older than I am, but when you see him you don’t know if he’s gonna whip out a pistol. Even if he doesn’t hurt anyone, you still don’t know is he gonna light the piano on fire. I mean, he’s probably the epitome of real rock ’n’ roll, with a good country background, and good boogie woogie.” If one had to pick a single touchstone for the Preacher’s music, it would be Jerry Lee Lewis, the prototypal country boogie man. Lewis, however, was a relative late-comer to the Preacher’s musical pantheon. Born 53 years ago in Malden, John Lincoln Coughlin was twelve when he fell in love with the king of glitz, Liberace. “It was a visual thing that I was getting off on,” he remembers, leaning across the table in his excitement. “It was kitsch, but it was so cool. He was almost on the borderline of being a rocker; he had that glamorous style of performing. I’ve always liked a good showman, even if the music can sometimes be secondary. Elvis could sing, ‘there’s a bump on a log, and there’s a frog on the bump on the log’-- now, that song doesn’t move me, but if Elvis were doing it, it would.” Of all Liberace’s playing, the Preacher loved his light version of boogie woogie. A novice pianist, he went to Cray’s Music in downtown Boston where “this very distinguished gentleman said to me, ‘If you like boogie woogie, have you ever heard Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson, Meade Lux Lewis?’ I said no; I didn’t know that era had even happened. He said “If you get off on Liberace’s left hand you better listen to the old boys that were the originators of this sound.’ The rest is history.” Young Coughlin became a record collector, and Ammons became his greatest pianistic influence, schooling his left hand to roll and swing like a big band rhythm section while his right There were two more figures to fill out the Preacher’s musical pantheon. The first was the king of the hillbilly singers, Hank Williams. “I love the way he sang,” he says. “And there are nights I can get my voice to sound almost like him. Not exactly his sound, but with his soul. He was the most heartfelt writer.” As with his other heroes, the Preacher not only listened to Williams but studied everything about him. “I do this,” he says, almost apologetically. “I exclude three quarters of what’s going on and I zoom in on one thing and obsess over it and I have scrapbooks full of pictures of Hank. I wrote to [his widow] Audrey Williams -- I said ‘This guy’s driving me out of my mind.’ I saw the cut of his figure and I felt a resemblance. I said this is spooky; if I were all decked out in white and a hat like him I would look exactly like that.” There is no such physical resemblance between the Preacher and his fifth god, and he seems almost regretful about the fact. “I don’t want to get too controversial,” he says. “But if I had been born female instead of male I would have loved to have been Mahalia Jackson, for even five minutes. I saw her face and watched how she handled herself with her bigness in her white choir robe.... Oh, what an immaculate woman.” So there it was: “I took all of Hank, excluded everything else, concentrated on Albert Ammons and Jerry Lee and I moved Mahalia in a front place and said ‘I’ll have one of these.’ It was close to the blues, but it wasn’t blues. It was rockabilly, hillbilly, boogie-woogie and black gospel music. I went from white Hank Williams thin as a rail to big black Mahalia singing ‘What a Friend We Have in Jesus.’” Ah, yes, the gospel. “I went into this other realm and I was into the Jesus trip and that’s how I got the name Preacher,” he recalls. “I was like a Billy Graham with a Jerry Lee, Albert Ammons left hand. Most of the sermons were at myself for either over-drinking or getting over-sexed. I was passionate as twelve bulls and yet having this great kind of Hollywood romance with Jesus.” Preacher Jack became a New England legend. His castle was the Shipwreck Lounge on Revere Beach Boulevard, where he held court for almost a decade. George Thorogood was a fan and brought him to Rounder, and for a moment it looked like he might find national fame. Instead, in the mid-1980s he set loose his band and settled into small solo gigs on the North Shore. These days, he plays Tuesdays and Fridays at O’Neill’s in Salem, Saturdays at Adel’s Restaurant in Middleton, and for the last month he has made it down to Cambridge every Thursday. It is a low-key schedule for a rock ’n’ roll wild man, but it has kept the Preacher alive, something that seemed a bit iffy in the heavy-drinking days of his youth, when he would go through a case of beer in a night’s work. “I’ve slowed down a little,” he says. “Some nights is more passion than others. Some nights I might get locked into something like a “Blueberry Hill” nostalgia trip Fats Domino set and people come in and they want you to rock the rafters like I did years ago. But I’ve mellowed a little. I’ve taken my piano a little more seriously, rather than just making faces. I think I’ve reached my pinnacle of boogie-woogie and now I want to try and get as much mileage out of it as I can.” As word spreads, old fans are drifting into Frank’s. Some seem almost regretful to see him looking healthy and drinking his beer at a reasonable rate. As the evening wears on, though, they find themselves drawn once again into his world, where a Hank Williams medley can lead into a religious rant that mutates into a bizarre meditation on the Michael Jackson-Lisa Marie Presley marriage, then slides easily into a wall-shaking tribute to Little Richard. “People like to be entertained,” he says. “They like my quips they like to hear me spout off something about Lisa Marie Presley or say something in politics. It doesn't mean a hoot and no one’s gonna take me too seriously—That's a good view preacher,” he remarks in a gruff voice, speaking to himself like a wise uncle, then continues: “You know, I like to socialize with my audience. I consider myself an entertainer. If I'd been more ambitious I probably would have been a good studio musician and just stayed with the piano and then kinda stepped back a little bit and been with groups and worked with them. But I got such a taste for being a front man that I almost dared to do anything, to ham it up, and just to keep the solo thing going.” His piano work has only improved with the years and, if his voice is rawer than in his youth, it sounds like he has earned every rasp and quaver. If customers enjoy his preaching as a sort of sideshow, he’s OK with that, but he’s also dead serious: “I looked at Hank Williams; he had so much talent, but he was addicted to a lot of things—whiskey, I mean heavy doses of stuff—and I said ‘Oh…’ That was scary. So I got over that casket syndrome and nailing myself to the wall, the martyrdom and I said, ‘I gotta concentrate more on the resurrection of Christ rather than the crucifixion.’ “I was like my own psychiatrist. I was analyzing, presenting myself with joy. Enjoying the music but trying to make every song I sang have some segment to my own life, and it worked. People would come in and almost have a religious experience with me. When I sang Hank I just became that kind of forlorn kind of an individual, and when I was doing Mahalia I became a black, powerful gospel female and I said, ‘Thou are going to the heights of heaven!’ I love characters, and it's not just the music, it's what the music does to get these people going.”

|

I did the interview below in 1995, a month after Preacher Jack began playing every Thursday night at Frank's Steak House, a few blocks from my place in Somerville.

I did the interview below in 1995, a month after Preacher Jack began playing every Thursday night at Frank's Steak House, a few blocks from my place in Somerville.  That was twenty-five years ago, and I haven't seen Jack in a long while. The last time was the night before my wedding, when I brought the mingled families to see him after the nuptual dinner. He was still playing strong in 2011, as witnessed in a

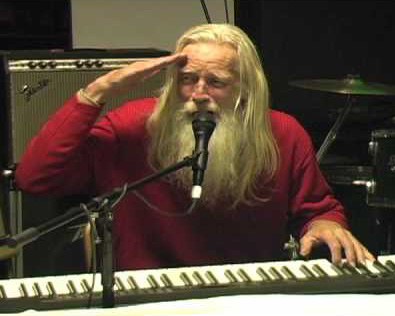

That was twenty-five years ago, and I haven't seen Jack in a long while. The last time was the night before my wedding, when I brought the mingled families to see him after the nuptual dinner. He was still playing strong in 2011, as witnessed in a  Even with his mouth shut, the Preacher is a commanding presence. He is six foot three and stiletto thin, dressed in black. His neat haircut, though less dramatic than the shaggy locks of yesteryear, only serves to accent a face that he accurately describes as “Lee Marvin’s younger brother with overtones of Mick Jagger.” He is friendly, almost courtly at times, and he clearly likes his audiences, but there is always a hint of danger, a feeling that Mr. Hyde is lurking somewhere behind his glittering eyes.

Even with his mouth shut, the Preacher is a commanding presence. He is six foot three and stiletto thin, dressed in black. His neat haircut, though less dramatic than the shaggy locks of yesteryear, only serves to accent a face that he accurately describes as “Lee Marvin’s younger brother with overtones of Mick Jagger.” He is friendly, almost courtly at times, and he clearly likes his audiences, but there is always a hint of danger, a feeling that Mr. Hyde is lurking somewhere behind his glittering eyes. wove lightning treble melodies. No sooner had he mastered the basics of boogie woogie then the rock ’n’ roll revolution hit, with Jerry Lee Lewis using the same musical language to tell a new, youthful story. “It all just came together and snowballed,” the Preacher remembers, his eyes gleaming at the memory.

wove lightning treble melodies. No sooner had he mastered the basics of boogie woogie then the rock ’n’ roll revolution hit, with Jerry Lee Lewis using the same musical language to tell a new, youthful story. “It all just came together and snowballed,” the Preacher remembers, his eyes gleaming at the memory. It feels strange to be watching a performer of his stature playing for a dozen or so people in a low-key neighborhood bar, but the Preacher seems satisfied. “I don’t have any regrets,” he says seriously. “I’m kind of a slow lazy person by nature, so I don’t have that desire to go out there with an ego of a Stallone and produce a film or anything. I feel comfortable living in Salem. I look forward to getting up every morning, have my three cups of coffee and open my eyes to the neighbors, say good morning to people, or just stand there in contemplation, listen to the birds chirping and maybe browse in the library a little bit. And then work at night and know that I’m still able to use my God-given hands and talent.”

It feels strange to be watching a performer of his stature playing for a dozen or so people in a low-key neighborhood bar, but the Preacher seems satisfied. “I don’t have any regrets,” he says seriously. “I’m kind of a slow lazy person by nature, so I don’t have that desire to go out there with an ego of a Stallone and produce a film or anything. I feel comfortable living in Salem. I look forward to getting up every morning, have my three cups of coffee and open my eyes to the neighbors, say good morning to people, or just stand there in contemplation, listen to the birds chirping and maybe browse in the library a little bit. And then work at night and know that I’m still able to use my God-given hands and talent.”