Elijah Wald – The G-Clefs |

| Back

to the Books and Other Writing page Back to the Archive Contents page By Elijah Wald © 1995 (originally published in the Boston Globe)

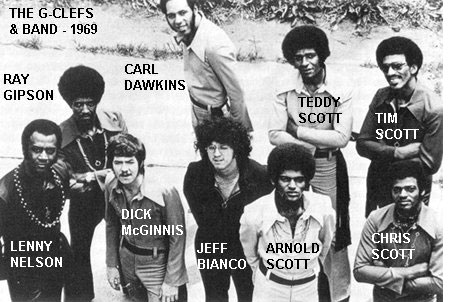

Forty years ago, the rhythms were a bit more sedate, the voices higher. Back then, the G-Clefs hung out on the corner of Northampton and Washington Streets in Roxbury, four brothers and their next door neighbor, putting the harmonies they had learned in St. Richard’s choir to new uses. Today the corner is gone, along with the elevated MBTA tracks that ran by the Scotts’ windows, but the G-Clefs are still going strong. A “greatest hits” collection is due out from Relic Records later this month, they are in the studio working on a new album, and Saturday they headline a rock ‘n’ roll show at Revere’s Wonderland Ballroom. “It’s really amazing that five men could be together all that time and haven’t killed one another,” Teddy Scott says, laughing. “Come pretty close sometimes, though,” Chris chimes in. Three of the Scotts and Gibson are sitting around Ilanga’s Roxbury apartment. Tim had to leave early, driving back to his home in Wareham, but the others are enjoying talking about the old days. They act like a family, finishing each others’ sentences and getting into mock scuffles. Teddy, the oldest brother and group leader, does most of the talking, along with Chris, who seems the most serious. Gibson plays the scrappy bad boy. Ilanga, born Arnold Scott, gestures with the theatrical grace of a dancer, his animated facial expressions accentuated by a touch of black eye-liner. “We started in the choir,” Chris says. “And we’d always listen to the Drifters and all them--The Dominoes, Five Keys...” Ray: “Flamingos.” Teddy: “The Swallows.” At that time, every corner had a group,” Chris says. “Or any place you had a hallway.” “For an echo chamber,” Teddy adds. “Then, you had Friday night social dances in the housing project function halls and different groups would go in and do their little bit, just to attract the girls.” First they called themselves the Bobolinks, one more in a long string of bird groups. Then they were the Clefs, and the Scotts’ mother suggested adding the G because they sang the Crows’ “Gee” so often. “It was a sign in music, but we didn’t know anything about that,” Teddy says. There was plenty of competition around Boston: The Love Notes, the Dappers, the Sophomores, even a calypso group called the Charmers, featuring Gene Walcott, who later changed his name to Louis Farrakhan. In the 1950s, being in a vocal group was a way of being cool. “It was no different than today,” Ilanga says. “The thing was, ‘I want the ladies.’ If you were a singer, you had it. If you weren’t nothing, a dude that sit on the corner...” “You didn’t even have to sound good,” Chris interrupts. “Long as you was in a group, the girls would be flocking to you.” “That’s why we always had a big gang,” Teddy says. “All the other guys would hang with us ‘cause all the girls were there. And to this day we still have a big gang.” Today, the gang is called the Band of Angels, and it is more of a social club. Gibson is wearing a Band of Angels hat, and Teddy shows off the logo on his wristwatch. Back then, though, they were the Victors. Their rivals were the Pythons, the Mustangs, the Shamrocks or the Red Raiders. Every gang had its turf and its colors. The G-Clefs talk about those days with relish, but are quick to point out that it was a different time. “It was just regular fights,” Chris says. “One gang against another, and if there was too many you’d run and, when it’s their turn to run, they’d run. You’d get your butt kicked and you’d wait for next week.” “We’d knock the dude down, give him a couple of kicks and go about our business,” Ray agrees. “You hit the street now, man, they’re coming out with guns. And we didn’t go around mugging people and stuff like that.” He pauses. “Not too much,” he adds, smiling.

“We were lucky,” Teddy says. “Because we had a New York producer, Jack Gold, and he knew the ins and outs of the radio stations. In those day you could walk into radio stations and disk jockeys, payola, everything was going on there. You could go and do little interviews on the air, and if the disc jockey liked you he could break your record in his area. You did every little radio station around: Lynn, Saugus, and you did the same thing around the country.” Soon the G-Clefs were out on the road, playing the “chitlin’ circuit” of black theaters: the Apollo in New York, the Howard in Washington, the Regal in Chicago, the Uptown in Philadelphia. “We Toured with everybody,” Teddy says. “And we were always in awe of the other people. We’d get to town and see the marquee and say ‘My God, we’re with Lloyd Price, we’re with the Drifters....’“ “Lloyd Price could not say ‘G-Clef’ to save his life,” Ray cuts in, laughing loudly. “Eclipse,” Ilanga mimics. “Eclairs,” Chris adds. “Anything.” Through the 1950s the group soldiered on, playing strings of one-nighters and rock ‘n’ roll package shows. Older groups like the Five Keys took them under their wings and taught them the tricks of the trade. By the early 1960s, though, things were changing. The payola scandals had hit, tainting rock ‘n’ roll with their revelations of bribery and corruption. The major record labels were playing it safe, steering clear of the classic street sound. While other top groups found themselves scuffling for record deals, the G-Clefs got lucky once again. “The majors wanted all the groups to do standards,” Chris says “Like the Platters with ‘My Prayer,’ which the Ink Spots had done in 1941. Because we were from Boston, we had that Northern sound. We could sound like the Mills Brothers, the Four Lads.” “We didn’t have a distinctive black sound,” Ilanga adds. “Because again we were in the choir so we had pronunciation, intonation, diction.” Jack Gold came up to Boston and had them try out a series of sweet songs, but nothing seemed to click. Finally, in desperation, they played him a novelty they had been fooling around with: Two group members sang ‘I Understand,’ a minor hit by the Four Tunes, while the others simultaneously sang ‘Auld Lang Syne.’ “Jack fell off the bed,” Chris says. “He said ‘Why didn’t you do that one right off? What are you guys, crazy?” “I Understand” put the G-Clefs in the top ten in 1961, and started a string of sweet ballad records. Though grateful for the success, they now seem less than thrilled by a lot of the songs. Then again, who could be thrilled by tunes like “There Never was a Dog Like Lad,” the theme from Warner Brothers’ Lad: A Dog?

It was a grueling schedule, with five 40-minute sets a night and ten on Sundays. It got so bad that they used to draw straws for who would go around the corner to a pay phone and call in a bomb scare to give them an hour off. They always sang “Ka-Ding Dong” and “I Understand,” but otherwise they stayed hot by moving with the times. Soul music had arrived, and the G-Clefs had risen to the challenge. Ray, whose family came from Georgia, had the Southern gospel sound of the great soul shouters. With him singing lead, the G-Clefs became a soul revue. “Whatever was a hit on the radio, we rehearsed it that afternoon, did it that night,” Teddy says. And the music was only part of the act. “Moves?” Ray asks rhetorically. “We were acrobats! I don’t know if we even had to sing, we did so many moves.” “We used be able to do an hour and a half, two hour show,” Chris says. “Everything that came on TV we made a comedy out of it. We’d paint our own sets. You know, we’re pretty industrious guys.” “We were the best dressed group you can imagine,” Ilanga says. “A lot of folks came just to see what we was wearing that night. Five shows a night and a different costume every show.” “And it would be three weeks before we wore the same one again,” Chris adds. “That was one of our fortes.” The stories start up again. The wild college gigs; the tour of Japan; the first time in Vegas, breaking the color barrier with their integrated backing band; the 20-minute version of “Hair,” complete with buckskin fringe costumes. Ilanga frequented Cambridge’s Club 47 with local folk star Jackie Washington, and added that flavor to the group’s sound. Then there were side projects, like Teddy’s record companies, G-Clef and Spotlight, which recorded the Gaines Sisters, one of whom later became Donna Summer, and the Ferrari’s, whose lead singer, Davey Jones, would soon join the Monkees. (“Talk about egos,” Teddy says. “You wanted to slap his face every time you looked at him.”)

Though the hits had stopped coming, the G-Clefs were riding high. Then, in the early 1970s, disco came along and changed the club scene forever. Jobs that had previously gone to full bands were now handled by one guy with a turntable. The G-Clefs had no interest in taking a major salary cut, so they broke up the group, went to college, and got other jobs. Chris went to work for Prudential. Teddy designed greeting cards for Hallmark before taking a job in the Arlington school system. Ilanga moved to Europe and became a successful Afro-jazz choreographer. Ray was the only one who tried to stay full-time in music, fronting his own group, Southbound. Nonetheless, whenever Ilanga was in town the G-Clefs would stage a reunion, and when he came back permanently in 1993 they decided to make a new go of it. They are, along with the Dells and the Four Tops, one of the three longest-lasting vocal groups in the business, and they figure they have enough experience to run a tight and profitable ship. Along with their own shows, they plan to produce other singers and try to help out younger musicians. They are excited about the new pieces they are recording, and every new gig finds them more confident. Most important, they say that the music is more fun than ever now that they don’t have to depend on it for their full income. “Oh, yeah, we’ve got a few businesses going,” Teddy says. “I rob banks. Ray drives the getaway car. He holds the old lady down, I get the pocketbook.” But seriously: “To me, music is something that nobody makes you do, it’s something you do because you love it. We five guys went our different ways, but we always knew where we were coming from. Now we’ve been together for forty years; if we can’t capitalize on us then forget about it. Might as well start digging ditches.” Watching the G-Clefs work an audience, it is easy to believe the new dreams will come true.”I look at the younger people,” Ilanga says. “If they start popping their fingers or moving their feet, then I know we’ve got it. When we’re on stage, I’ll find somebody just sitting there like this.” He crosses his arms and frowns. “I want to know why this man isn’t feeling what we’re feeling. And I’ll work him. Work this fool. Get him. Because, you get him and you’re home free.” And, as far as they are concerned, the group can keep going another forty years. “I have a friend she said, ‘It’s gonna be gorgeous girls coming out, pushing the G-Clefs in wheelchairs.,”‘ Ilanga says. “I said yeah, that’s definitely the trip. Why not?” “You go to hell,” Ray growls. “I’m gonna be walking.”

|

The G-Clefs explode onto the stage, five singing, dancing dynamos in sparkling white suits with red ties and cummerbunds and gold G-Clef pins. Tim (Pay-me) Scott has a hard, churning rhythm going on his Gibson guitar. Teddy and Chris Scott add sweet harmony, with Ilanga between them, shaking and twisting like he was on fire. Ray (“I’m small, but I’m mighty”) Gibson is in front, shouting with the passionate energy of a soul king.

The G-Clefs explode onto the stage, five singing, dancing dynamos in sparkling white suits with red ties and cummerbunds and gold G-Clef pins. Tim (Pay-me) Scott has a hard, churning rhythm going on his Gibson guitar. Teddy and Chris Scott add sweet harmony, with Ilanga between them, shaking and twisting like he was on fire. Ray (“I’m small, but I’m mighty”) Gibson is in front, shouting with the passionate energy of a soul king.  They didn’t have to. Despite their humble beginnings and a debut appearance at Revere’s Rollaway Ballroom that found them so petrified with stage fright that they could hardly sing, the G-Clefs were the first Boston vocal group to break into the big time. The song was “Ka-Ding-Dong,” a peppy doo-wop number that rocketed up the charts in September 1956.

They didn’t have to. Despite their humble beginnings and a debut appearance at Revere’s Rollaway Ballroom that found them so petrified with stage fright that they could hardly sing, the G-Clefs were the first Boston vocal group to break into the big time. The song was “Ka-Ding-Dong,” a peppy doo-wop number that rocketed up the charts in September 1956. “We couldn’t do what we wanted to do; it was a whole bunch of foolish songs,” Chris says. “They would always get us to the studio, but when the record came out they put it at the bottom of the pile. Then we stopped making records after ‘64, because the Beatles and all that came in, the English sound. We were working hard, though: twelve months a year, seven days a week.”

“We couldn’t do what we wanted to do; it was a whole bunch of foolish songs,” Chris says. “They would always get us to the studio, but when the record came out they put it at the bottom of the pile. Then we stopped making records after ‘64, because the Beatles and all that came in, the English sound. We were working hard, though: twelve months a year, seven days a week.” Most of the time, the G-Clefs worked close to home. Boston was one of the highest-paying cities in the United States, and the G-Clefs were kings of the local club scene. They were a tightly organized unit, with salaries, equipment and rent paid by the organization and fines for everything from drinking to losing a G-Clef patterned cuff link. Ilanga, the group’s treasurer, recalls that it was ten dollars a minute if someone was late to rehearsal, and Ray moans as he remembers how many uniforms the group bought with his losses.

Most of the time, the G-Clefs worked close to home. Boston was one of the highest-paying cities in the United States, and the G-Clefs were kings of the local club scene. They were a tightly organized unit, with salaries, equipment and rent paid by the organization and fines for everything from drinking to losing a G-Clef patterned cuff link. Ilanga, the group’s treasurer, recalls that it was ten dollars a minute if someone was late to rehearsal, and Ray moans as he remembers how many uniforms the group bought with his losses.