Elijah Wald – Folk,Country, and Gospel pieces

[Home] [Bio] [Jelly Roll Blues] [Robert Johnson] [Dave Van Ronk] [Narcocorrido] [Dylan Goes Electric] [Beatles/Pop book] [The Dozens] [Josh White] [Hitchhiking] [The Blues] [Other writing] [Musical projects] [Joseph Spence]

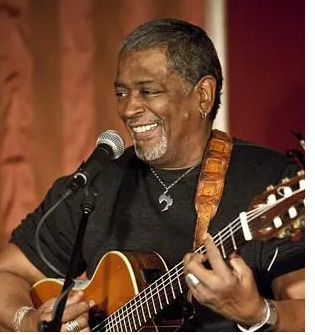

Jackie Washington/ Jack Landron (1997)

By Elijah Wald

The billing is oddly appropriate: "The Return of Jackie Washington,

starring Jack Landron." Landron is a New York-based, Afro-Puerto

Rican actor. Washington was the king of the Cambridge folk scene,

"the male Joan Baez." Both were born in Roxbury and named

Juan Candido Washington Landron; except for a temporal gap of thirty

years, they are the same person.

The billing is oddly appropriate: "The Return of Jackie Washington,

starring Jack Landron." Landron is a New York-based, Afro-Puerto

Rican actor. Washington was the king of the Cambridge folk scene,

"the male Joan Baez." Both were born in Roxbury and named

Juan Candido Washington Landron; except for a temporal gap of thirty

years, they are the same person.

The billing was Landron's idea: "It's a very glib thing, but the more I think of it, that's really what it is," he says. "I have not done this in a long time, and I found that if I approached it as me playing Jackie Washington I was not daunted. So I am having a wonderful time going 'Oh, yeah, he used to do this,' and 'Oh, wasn't that funny when he used to say that.' And also comparing how I felt when I sang or worked up a certain arrangement with how I think about those things now.''

In the early 1960s, Jackie Washington was a folk star. He sang everything from English ballads to calypso, and he had an energy and humor that carried audiences along with the force of a tidal wave. In recent years, he has made occasional visits to his old haunts, playing a song or two at gatherings of the local folk clan, and he still has the same explosive energy and the same gentle way with a melody. Nonetheless, his appearance at Club Passim this Saturday will be his first full-scale concert in many years.

Despite the billing, Landron will be doing a lot more than recreating his youth. In the intervening years, he has become a versatile songwriter, and his show will feature material he has composed for National Public Radio, the Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre, and a new musical, "13th St. Suite." Still, he finds the experience extremely nostalgic, and it has got him thinking about old times.

Landron became a folk singer completely by chance. He was a student at Emerson college, with plans to be an actor when he and "a bunch of my little Ivy League bourgeois friends from Roxbury'' went down to a Boston coffee house, the Golden Vanity.

"We were a group of Cape Verdian, Puerto Rican, black guys, and we all had on our little three-button suits and those skinny little ties and Oxford shirts,'' Landron remembers. "We went in, and there was nothing on the menu but different kinds of coffees, teas and cider, and the people were strange. There were all these white types, and they were dressed like 'Oh, we don't care about looking good or anything like that.' We were having a wonderful time--little did we realize that Darjeeling or Lapsang Suchong, that [stuff] was expensive.''

Landron had the solution. "It was a 'hoot night,' so if you performed you could get your drinks free. I went up there and did some stuff I had learned off Harry Belafonte records, and I was a hit.''

Landron became a regular at the Vanity, then moved across the river to Cambridge's Club 47. It was the height of the folk revival, and he was a unique character, a young, vibrant, black performer who could sing just about anything and make audiences love it. It was an exciting time, when Bob Dylan could pick up his version of the ancient ballad "Nottamun Town'' and rework it as "Masters of War,'' or a Portuguese song he was featuring could show up on the hit parade as "Lemon Tree.''

Somehow, though, Landron never made it as big as a lot of his peers, and he firmly ascribes this to the racial climate. "This was even before the days of tokens,'' he says. "You were just invisible. You wouldn't open a magazine or turn on the TV and see black people or anything Puerto Rican. Everything was 'Leave It To Beaver.' So I know that I was patronized. I know there was a limitation on what I could do. I made some innovations that found root, but there was not a way for a guy like me to be really influential. I was an exotic trifle. That was what that time was like.''

Matters came to a head when Landron went south to work for black voter registration. Other folk singers came, sang, and went home, but he stayed and organized. When he returned to Cambridge, things did not feel the same. Meanwhile, folk-rock had hit, and his acoustic style was out of favor. Landron decided to make a break with his past. He moved to New York, changed his name, and entered another world.

"I worked at the Puerto Rican Traveling Theater, the Negro Ensemble, the Caribbean-American Repertory Theater. I was playing in non-white theater companies, to largely non-white audiences. New York is very much different from Boston, in that there are whole enclaves where you can be submerged in a culture, and that's what happened to me.''

Though there is a sharp edge to some of his reminiscences, Landron says he is anything but bitter about the past. It was, as he will point out, his youth, and he is looking forward to revisiting it tomorrow evening. He is bringing his daughter, who has never seen him perform as a folksinger, and plans to drive around Roxbury with her and point out the sights of his childhood.

He is also enjoying reimmersing himself in the music. For his occasional guest spots he has relied on his humor and stage presence to wow the audience, but this time he wants people to hear the songs. "I have been working on putting together this show,'' he says. "I'm going to try to do some real music, really sing some stuff. Also, looking over the things and reminiscing, there are stories that go with the songs that are interesting. So I'm looking forward to it very much.''

Back to the Archive Contents page

By Elijah Wald

James Hill will turn 81 a week from today. It is not an age when most people are doing rock 'n' roll shows, but Hill's group, the Fairfield Four, will be opening for John Fogerty at Harborlights this Sunday, and joining him for two numbers, including "A Hundred and Ten in the Shade,'' the song they sing on his new "Blue Moon Swamp'' album.

"Oh, it's been going great!'' Hill says of the Fogerty tour. "I wondered about it, 'cause we sing an a cappella gospel, you know? And they got a rock 'n' roll band, man. It's two different things, but man, people act like they really is enjoying their opening act on this one; they don't want us to stop singing.''

The Fairfields' recent list of collaborators is impressive. In the last three years, they have worked with Lyle Lovett, Elvis Costello, Steve Earle, Charlie Daniels and Lee Roy Parnell, and they had to break the Fogerty tour to go into the studio with Johnny Cash. Meanwhile, their own new album will be out in September, with an all-star release show scheduled at Nashville's Ryman Auditorium.

Ask Hill how he accounts for the group's success, and he sounds pleasantly puzzled. "I'm surprised the young people are liking what we are doing,'' he says. "But they really love it. I think it's new to them, just like rap is. You catch a guy 30, 35 years old, what we're doing now is different from anything he's ever heard. But we're doing the same thing we did when I came to the group in 1946.''

The original Fairfield Four got together in the early 1920s, but they hit their peak in the 1940s, with a radio program on Nashville's powerful WLAC that could be heard all over the country. By the end of the decade, they were one of the best-known groups in gospel, featuring Sam McCrary's lead, Hill on baritone, and the booming bass of Isaac Freeman, the only other early member still with the group.

The Fairfields were something of a supergroup, formed by raiding the best singers from other outfits. Hill, for example, had started out singing with his mother's gospel group and gone on to achieve success with a Birmingham quartet, the Five Silver Kings ("quartet,'' in gospel terminology, is a style of singing, and by the late 1940s virtually all quartets had five members). "What the Fairfields were singing was right down my alley,'' he says. "So I fit right in.''

That golden age was of short duration. In 1950, Hill and Freeman split off and formed another group, the Skylarks. "I'll tell you what happened,'' Hill says. "Gospel had hit a hard place in the road, man, we weren't doing nothing too much. And, believe it or not, for 30 years we didn't do nothing too much but just every once in a while we'd get together and do a number or two, an anniversary or something, but that wasn't too often.''

It was in 1980 that the Fairfields reformed, at the urging of gospel scholar Doug Seroff. "He got us to go to Birmingham, Alabama for a quartet reunion thing, with a bunch of older groups. So we got together and went on down there, but we didn't think the people were gonna think too much of us, because at that time the groups had gone contemporary mostly, they'd added drums, guitar, keyboards, all of that stuff. I said they wouldn't want to hear us, especially since we're men getting up in age too. We went down there to sing, man, and they didn't want us to stop singing.''

That led to several performances at the Smithsonian festival in Washington, as well as to Carnegie Hall, the New Orleans Jazzfest, and hundreds of smaller venues. In 1992, their first modern album, "Standing in the Safety Zone,'' was nominated for a Grammy, and they made a national tour with Lyle Lovett. The next year, Elvis Costello took them to London's Queen Elizabeth Hall, and they have barely rested since.

Last year, the Fairfields added a new lead singer, Joe Rice. At 23, Rice is young enough to be the grandson of the other members, but Hill says he fits in perfectly. Meanwhile, Hill himself is still going strong, and has no plans to retire anytime soon.

"I intend to just keep on doing what I've always done,'' he says. "You know, time brings about a change; I don't get around as much as I used to do; but as far as singing goes it's no problem. Long as I be able to do it, I'm going to do it.''

Back to the Archive Contents page

By Elijah Wald

Globe Correspondent

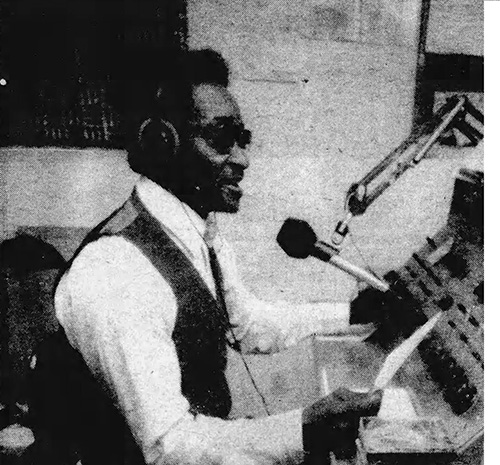

David Adams is on his feet in the WILD broadcast studio, swaying

and clapping along to the new disc from the Soul Stirrers. A photographer

scrunches in the corner, snapping off shots. As the song ends, Adams

slides into his seat, fades the music down, and hits the red "talk''

button. "Ohhh!" he hollers. "They're taking all kinds[MAKE

ITAL] of pictures in here! They're gonna make David a star!'' With

practiced ease, he flips a cart into the tape deck, and an advertisement

comes on for his Saturday night anniversary concert. He turns the

mike off, reaches for another CD, looks up at the photographer,

and laughs.

David Adams is on his feet in the WILD broadcast studio, swaying

and clapping along to the new disc from the Soul Stirrers. A photographer

scrunches in the corner, snapping off shots. As the song ends, Adams

slides into his seat, fades the music down, and hits the red "talk''

button. "Ohhh!" he hollers. "They're taking all kinds[MAKE

ITAL] of pictures in here! They're gonna make David a star!'' With

practiced ease, he flips a cart into the tape deck, and an advertisement

comes on for his Saturday night anniversary concert. He turns the

mike off, reaches for another CD, looks up at the photographer,

and laughs.

Outside the studio's glass window, in the front office, Alice James is answering the phone. The president of the David Adams Fan Club, she is there with him every Sunday morning from dawn to nine o'clock, taking calls from local ministers, song requests, dedications, and news of births, deaths, and illnesses in Boston's gospel community.

Though little known to the outside world, within that community David Adams is already a star, and a familiar friend. Next year Adams, 63, will celebrate his 30th anniversary as Boston's best-known gospel d.j. Known as "Mr. 'My My My,' '' for his trademark catchphrase, he has become a Sunday morning institution, the area's most enthusiastic booster of old-time gospel music.

Asked to explain his enduring popularity, Adams gives a typical response: "The only thing that I can say is it's gotta be in the soul. As I tell people, I'm not ashamed -- if I feel the spirit I'm gonna shout. God has blessed me that way. He's been a great blessing to me. I'm not looking be a star. I'm not looking to do anything but give God praises, and if I can just can help one person along the way, then my living will not have been in vain.''

It may sound trite to some, but Adams clearly means every word, and anyone in Boston gospel will testify that he lives by his message. It is the old-time way, learned during his boyhood in the south. "If you speak about my history,'' Adams says, "I'm from Florence, South Carolina, and I started singing with my brothers' group when I was about eight years old. I stayed with gospel music and I knew all the original groups. I knew the names of the singers like some kids know baseball players. I came from South Carolina into Philadelphia, I sang with a group there for about nine years, and then I left Philadelphia and came up here. Boston was a beautiful place, so that made Boston my home.''

Adams arrived in 1959, and quickly became a familiar face around the gospel scene, doing a little singing and turning up at programs by all the local groups. Then, in 1968, he found himself in a community organization, the Black United Front, that was confronting the owners of WILD. In a scene that was being duplicated across the country at stations that served black listeners, the group demanded that the station place blacks in management positions rather than simply using them as on-air frontmen. WILD capitulated, and brought in Paul Yates from Pittsburgh to be general manager.

"When he came here, there was no gospel on for three mornings and I called him up and told him there was no way that we could do that,'' Adams says. "The community wouldn't accept that. So he said 'Well, I just got here and I don't know; would you come down and talk with me?' So I went down and he and I talked and he says, 'Could you take the job?' ''

Adams at first demurred, as he did not have a broadcasting liscence, but Yates brought him in to do a one-hour show presenting local singers while he studied and got his papers in order. As soon as he passed the exam, he became religious director for the station, and stayed there for the next 15 years, going on the air at dawn, seven days a week.

The hours sound grueling, but Adams seems to take a sort of pleasure in the task. He gleefully recalls the blizzard of 1978, when the National Guard had to give him a lift down to the station. The snow was chest-high, but he was on the air at dawn.

"As soon as I signed on, I saw the hot line ringing and I knew it was [then manager] Sunny Joe White. He says, 'David, I don't know how you made it.' And he says, 'I don't know how I'm gonna get down there. Could you stay until I get there?' I says, 'Yeah, I can stay till you get here, but don't you dare ask me. . . .' I says, 'You know what I mean.' He says 'Aw, I'm not gonna ask you nothing. Just play your own music, David. I know you ain't gonna play no rock and roll'. And I says, 'You know right.' So, I played my gospel music, let everybody know that they couldn't use their cars. He made it there about 11:00 and I made it back home.''

Adams stayed at WILD until 1983, when he got a daily show on WCAS (later WLVG), an all-gospel station. He was the station's top draw until 1987, when an aneurysm almost killed him, and forced his retirement. He remained visible on the scene, though, with benefit concerts and appearances as an m.c., and he returned to WILD with a Sunday morning show in 1991. The original arrangement was that he would be paid in advertising for his concert presentations, but his doctor forbade him to get involved in that high-pressure business. So, for six years, he and James have dragged themselves out of bed before dawn every Sunday for the pure love of the music and the community.

"It's just something I got to do,'' he says. "I can't let it go. So many of the ministers in this city, I knew them before they ever were into the ministry. They knew me before I started broadcasting. It's just like a home family. It's a beautiful feeling, and the music to me is very, very important because it is an expression of life.''

And, for now, at least, he has no thought of giving it up. "I tell you, I don't never want to retire from radio,'' he says, sounding as enthusiastic as he does on the air. "If the good Lord says one day that my work is done, then I will be ready to retire. But, until that day, I'm gonna try to haul right on until the end.''

Back to the Archive Contents page

Buckwheat Zydeco/ Rosie Ledet (1997)

By Elijah Wald

Globe Correspondent

It's zydeco time in New England. Sunday, Stanley (Buckwheat) Dural brings his band to Decordova Museum. Wednesday, "Zydeco Sweetheart" Rosie Ledet is at Johnny D's. Then, next weekend, the Cajun & Bluegrass festival in Escoheag, RI, features Ledet and C.J. Chenier along with over a dozen other bands.

For those who have not heard it, zydeco is the African-American counterpart of Cajun music, a spicy mixture of Cajun, blues, r&b, and whatever else a musician may care to toss into the pot. Pioneered by artists like Boozoo Chavis, Rockin' Dopsie, and the king, Clifton Chenier, it swept the world in the Cajun craze of the early 1980s.

One of the most exciting places that the music began to catch on was among young, black Louisianans. For years, they had tended to regard it as old folks' music. "My dad played zydeco music for family entertainment in the home,'' Dural recalls. "He played the real traditional style, only with accordion and washboard. Just for family gatherings, which we call a boucherie[ITAL] -- kill a pig, get outside, the fathers would play the music and the mothers would do the cooking. He always wanted me to play the accordion, but I was like in my generation. The accordion was an older generation. That's how I felt; I was one of the biggest critics of zydeco.''

Dural was a local r&b star, the organ-playing leader of Buckwheat and the Hitchhikers, playing the sounds of P-Funk and Earth, Wind and Fire. Then, one day in 1975, he took a one-night gig backing Clifton Chenier. "I learned something there,'' Dural says. "What you don't understand, you don't criticize. What got me was the energy. We played four hours non-stop and it felt like 30 minutes, that's how excited I was. I didn't know it could have that much energy, because I'd always heard it played at the house with just my dad and the washboard, but Clifton had guitars, bass, drums and horns, and man, I couldn't believe it.''

When Dural was discovering zydeco, Ledet was only four years old. Like him, she grew up thinking of zydeco as her parents' music, but by the time she was in her teens Dural had built a bridge for younger listeners. "I love him,'' she says enthusiastically. "He's much more rocky.''

Dural's funk-r&b background informed his zydeco style, horrifying the purists but winning a new generation of local kids. As Dural points out, this was exactly what Chenier had done a quarter-century earlier: "Clifton also took it to a different dimension; he had blues, roots culture, a little rock 'n' roll. And I took it up a step higher, to my generation. You know, I'm not gonna have no limits to my abilities. If you can do it, why not?''

In an odd turnabout, the younger generation that Dural brought to the field has now moved the music towards an older sound. Rather than playing the piano accordion favored by Chenier and Dural, Ledet and her peers tend towards the older button accordion, either the classic one-row instrument or the somewhat more sophisticated three-row. "I like the piano too,'' Ledet says. "But they're so heavy and hard to handle. To me, it's just a lot easier to play the little push-button. And back home, it's just kind of what's happening right now.''

Dural finds this pretty funny. He stresses the greater versatility of the piano accordion's chromatic keyboard, but also says that, as an organist, he found the more primitive instrument insurmountably foreign. "I wouldn't even dare try to challenge that button accordion,'' he says, laughing. "Buttons in the back, buttons in the front, man, too many buttons for me. It gives me the blues.''

Whatever they play, though, he is thrilled to see a new generation entering the field. "There are so many young people in zydeco now, and it's a good thing, 'cause when the roots of your culture is lost, man, you lose your identity. If you stay away from the roots of your culture and your music just to make a dollar bill, it's defeating the purpose.''

To drive the point home, Dural has just recorded the most traditional-sounding album of his career, "Trouble.'' Though all but one song, a version of Robert Johnson's "Crossroads,'' are originals, he is hearking back to the sound of those back-yard barbecues of his childhood, the rhythm-heavy, chugging sound that has found new life in the hands of modern Louisiana stars like Beau Joque. "This is the beginning,'' he says. "Like rock 'n' roll come out of the blues. It's spiritual. No matter where you want to take it, you always got to have a beginning.''

It is also a tribute to his father, with whom he had a difficult early life, but reconciled through music after he became a zydeco player. For black French Louisianans, as for their white Cajun counterparts, the music is not only exciting, but also a bridge to their heritage.

"My parents love it!'' Ledet crows. "They couldn't believe it at first, cause I was one of those kids who were like, 'Nah, I don't want to listen to that. I hate that.' And they're, 'I'm telling you, it's good music.' They was always trying to get me interested, but I was more into rock 'n' roll and blues. But I love it now, and a lot of younger people are really[ITAL] getting into it. So that's going to keep the tradition alive, and help it to grow.''

Back to the Archive Contents page

Elijah Wald

Globe Correspondent

Austin, Texas, has been the most fertile ground for folk/country/rock fusions in the United States, but even by Austin standards the Bad Livers are unusual. An acoustic trio, led by banjo player, singer and songwriter Danny Barnes and largely devoted to old-time, traditional styles, the band has developed a hard-core following centered in alternative rock venues. Its last Boston visit was as opening act for the Butthole Surfers. Tonight, it headlines at the Rat.

The odd thing about this is that the Bad Livers do not sound particularly odd. There have been comparisons to the Pogues, but the Bad Livers have none of that band's obvious mix of traditional material and punk attitude. "We're not shtick-oriented,'' Barnes says. "We didn't have a meeting and decide how we were gonna dress or what the market needed. We are just totally music driven.''

Bass and tuba player Mark Rubin concurs. A versatile musician who seems to have worked with half the roots bands in central Texas, he says he and Barnes just started fooling around with a lot of music they enjoyed and the band formed naturally out of their experimentation. "It wasn't like an epiphanal moment or anything,'' he says. "It just organically grew, like a fungus.''

Three things set the Bad Livers apart from most folk or country roots bands. One is their range of influences: Rubin comes from Stillwater, Oklahoma, and grew up around classical music and traditional jazz, then went on to rock, country, bluegrass and Tex-Mex (he currently plays bass for Santiago Jimenez). Barnes is from Denton, Texas, and grew up in a family that worshipped country music, which he mixed with blues, western swing, and whatever else caught his fancy. When they got together, they were delighted to find that they could make this hodge-podge work as a unified whole.

The band's second strength is the technical facility of the musicians: Rubin jokes about his choice of instruments ("In Oklahoma, if you're a large-statured gentleman, they either put you on the bass or the tuba''), but he provides a rhythmic foundation that is both understated and distinctive, slapping his bass like a bluegrass old-timer or making his tuba sound like a jug. Barnes plays six instruments on the band's latest reocrd, and is a virtual encyclopedia of traditional banjo styles. Meanwhile, Bob Grant, a new member, keeps the center together with strong rhythm guitar and mandolin.

Then there is Barnes' composing and arranging. It is misleading to call him a songwriter, because the raw song is only part of the sound he assembles. Rubin enjoys a comparison with Duke Ellington, who wrote pieces for the specific talents of his musicians. Barnes describes the process as "a symbiotic relationship, in that I get my songs out there and the band gets custom-made songs to fit what they're doing.''

The songs are all original, and range from quirky stylistic fusions to pure, traditional-sounding numbers like "Corn Liqour [sic] Made a Fool Out of Me,'' which sounds like it could have come from the 1920s string band master Charlie Poole. Barnes enjoys experimentation, but is equally proud of his ability to write in the classic styles; to him, learning to write like the masters is as much a part of the process as learning their instrumental styles, and he takes the comparison to Poole as a huge compliment. ''I consider those Charlie Poole tunes to be as good as anything anybody's ever done,'' he says. "That music goes beyond the form. It has a sort of psycho-acoustic effect, like I assume Middle Eastern music has. It seems to speak to us beyond our time, like the voice of God.''

As a banjo player, Barnes may have a special affinity for Poole's work, but he is equally effusive in his praise of musicians from quite different worlds: Bob Wills, T-Bone Walker, or Roky Erickson, of the Thirteenth Floor Elevators ("he had a jug player in a psychedelic rock band--way ahead of his time''). To him, it is all of a piece: it is good music, and genre need not come into the discussion.

Because of this musical omniverousness, neither Barnes nor Rubin express any particular surprise that their rootsy, acoustic sound should have become popular with the alt-rock crowd. After all, if they are good, why shouldn't people enjoy what they play? "When we walk on stage, what we think about is the music,'' Barnes says. "We don't think about the audience at all. We think about each other. We're real, super-duper music fans, and we say 'Hey, look, if we can entertain and impress ourselves, and have fun and interact, then we're gonna be fine, whether or not they like it.' And, 99 percent of the time, they get off on it even more because they realize we're not putting anything on, we're doing this because we believe in it. They get into the energy and feeling we put into our music, and we end up being greatly rewarded.''

Back to the Archive Contents page

By Elijah Wald

LEICESTER, MASS. -- Big Al Downing comes down his driveway exuding

warmth and friendliness. He is a huge man with a big smile, outfitted

in comfortable cowboy wear: wide-brimmed white hat, studded denim

jacket and worn leather boots. He brings the visitor into his ranch

house, located on a quiet back road, where he moved some years ago

to be near his wife's family. Downstairs, in his basement studio,

the walls are covered with pictures and awards: Downing with various

country stars, or a plaque proclaiming him Billboard Magazine's

Number 1 New Country Artist of 1979.

LEICESTER, MASS. -- Big Al Downing comes down his driveway exuding

warmth and friendliness. He is a huge man with a big smile, outfitted

in comfortable cowboy wear: wide-brimmed white hat, studded denim

jacket and worn leather boots. He brings the visitor into his ranch

house, located on a quiet back road, where he moved some years ago

to be near his wife's family. Downstairs, in his basement studio,

the walls are covered with pictures and awards: Downing with various

country stars, or a plaque proclaiming him Billboard Magazine's

Number 1 New Country Artist of 1979.

The award memorializes Downing's fourth adaptation to the changing tides of American music. By the late 1970s, he had already hit in rock 'n' roll, soul and disco. Today, though, he is best known as the top African-American hitmaker in the country field after Charley Pride, and he will be at Johnny D's in Somerville this Thursday headlining a black country bill that also includes Bobby Hebb (of "Sunny" fame) and Barrence Whitfield.

Though to some people the idea of a black country singer seems strange, Downing says that is a misperception. "When I was growing up in Oklahoma, we'd go in the black clubs and they'd be playing harmonica and stuff, and blues and country,'' he says. "My dad used to listen to the Grand Ole Opry, and we used to work in the hay fields -- we were contracted to load tractor-trailer semis that would come up from Texas -- and all they played was country music all day long.''

The history of African-Americans in country-western music was highlighted

last year by "From Where I Stand: The Black Experience in Country

Music,'' a boxed set from Warner Brothers Records that featured

Downing, Hebb, and Whitfield along with dozens of other black musicians

and singers. Of all the artists included, Downing has the longest

pedigree in the field. Back in the mid-1950s, he was already touring

with a white rockabilly band, Bobby Poe and the Poe Kats, and touring

with country-rockabilly star Wanda Jackson.

In 1958, with Downing singing lead, the Poe Kats cut a rockabilly

classic, "Down On the Farm,'' and began touring out of their

home area of Oklahoma and Kansas. Bizarrely, their first gig was

in Boston, playing in the Combat Zone.

"I'll never forget it, because we made $90 a week,'' Downing says, chuckling. "Back in Oklahoma we would work one day a week for three hours a night and make seven, eight dollars, and we'd split that among four of us, right? When we came east we worked seven days, and on Saturday we worked one in the afternoon to one at night, and we made $90 a week. That was the big time.

"I remember one club there -- we were sitting there our first night, waiting for the other band to tear down so we could set up, and the other bandleader went over to the club owner and said, 'We're finished, now I want to get paid.' And the guy said, 'OK, hold out your hand.' The guy held out his hand, and the owner picked up a baseball bat and cracked him across the knuckles as hard as he could. Bam! He said, 'We didn't like you here, so that's all you're gonna get paid.' Really, man. So we said 'Wooow! What if he don't like us?' ''

Fortunately, Downing was an immediate favorite, though the club

owner insisted on billing him as Big Al Domino to capitalize on

his resemblance to Fats Domino. "I said, 'My name is Downing.'

He said, 'No, it's Domino.' Oh, man! So that was my first trip to

Boston.''

As Downing sits back in his chair, the stories just roll out. He

has been a professional musician since about 1955, when he was 15,

making his way in a world where he was often viewed as an outsider,

but as he talks the smile virtually never leaves his face. Not that

the experiences were always funny.

"I ran through that whole gauntlet of prejudice,'' he says. "We played places where there wasn't even a black man in the town. I'd have to go to a different restaurant to eat, and a lot of times the band would have to throw a blanket over my head and carry me into the hotel room. I took all the prejudice and all the people saying, 'Man, you're crazy to do this.' Bobby Poe warned me, he said, 'We got those people out there that just don't like black people working with white people together -- specially you working with Wanda Jackson, you know, a girl -- you're gonna get some really big flack for that.' And I said, 'Let's take a chance. I don't care, 'cause I want to play music.' That's all I was concerned about.''

Downing toured with the Poe Kats into the early 1960s, then he and fellow Kat Vernon Sandusky went on, with Poe as their manager. The original concept of the band had been to cover the full gamut of rock 'n' roll, with Downing covering the hits of Domino and Little Richard while Poe sang the Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis numbers. Over the years, though, Downing had proved his solo power, recording a Domino-styled session in New Orleans with a crew including Dr. John and hitting the charts in 1963 in a soul duet with Little Esther Phillips.

Nonetheless, he continued working with his white partners until 1964 and, for once in the conversation, Downing seems genuinely bothered as he remembers the break-up. "There come a time when they had a big record, the band without me. They were called the Chartbusters, and 'She's the One' was the name of the song. The Beatles had come out and all that white music was happening, and they said, 'Al' -- now, all of this time I'm carrying the band, you understand, through thick and thin -- and all of a sudden they said, 'We can't use you in the band because you're black, and we want to go to the white audience.'

"I said, 'Oh, man.' What a trip that was. So I just got out of it completely and I went out and got a soul band with me and my brother. We called ourselves Willie and the Brothers and we did Sly and the Family Stone and played all the big colleges and stuff. We did some recordings, and then we met a guy named Tony Bon Jovi, who's Jon Bon Jovi's cousin or uncle or something, and he said, 'I like your band, and I like you Al. I'd like to cut a record of you.' This is in '67 or '68, and we tried different things, me and my brother tried to cut like Sam and Dave and all of that stuff and it just didn't work out. Then we come on up to the disco era and Tony said, 'Al, try to write a disco song, man.' So I came up with this song called 'I'll be Holding On' and it was a big number one disco record in '75.''

Downing seemed to have found a new career in the r&b world, but there was a surprise in store. He and Bon Jovi went into a New York studio, trying for another disco hit, but none of the songs seemed quite right. "After about two hours we said, 'Let's take a break,' and everybody left and I went in and sat down at the piano and I started playing 'Mr. Jones,' 'Touch Me' -- just me and my piano, sitting there messing around. Tony happened to be in there at the board, listening, and he opened the mike and said, 'What's that you're playing?' I said, 'That's my country stuff.' He said, 'Man, that's great stuff, has anybody cut any of that?' I said 'No,' and about 20 minutes later he came back and said, 'Hey, forget disco, we're gonna cut that.' ''

"Mr. Jones,'' a story-song about a black sharecropper who raises a white orphan, was Downing's entree to the country charts in 1978. In 1979, he hit even bigger with "Touch Me,'' and went on to place another fifteen records on the charts over the next decade. Naturally, he was compared to Charley Pride, then the only black star in the field, but Downing is quick to point out the difference in their styles.

"I never wanted to go the way he went. See, Charley Pride went strictly country: When you hear him, it's just like hearing a hillbilly guy from Arkansas. I didn't want to do that; I didn't want to loose my roots. Because I grew up listening to WLAC [a famous r&b station] and Sam and Dave and Otis and all of those people. So even when I do country I still keep a little bit of soul in there. I did not want to lose that heritage, because look at all the music I would miss: I couldn't play Ray Charles or Fats Domino or Otis, and hey, I don't want to miss that music.''

Downing thinks that his r&b material may turn a few country listeners off, but, if so, they need to broaden their view of the music. "A lot of people don't realize that country is everything. I mean, when you hear George Jones and them people you don't get just strictly twang. Man, they do some soulful singing. So I said, 'I'm doing my kind of country. I don't want to sound like anybody else. I want to sound unique and different.' And it's turned out real good that way.''

Today, Downing tours the country fair circuit throughout the South and Midwest, and goes to Europe a half-dozen times a year. He has been off the charts for quite a while, but continues to write country songs, and the Warner Brothers set has brought some queries from Nashville. Meanwhile, he is cutting a new album and carrying European CDs of his older hits to sell to the hardcore fans.

He would like to get another hit, but realizes the present climate is less than ideal. The barriers Pride broke down are up again in force, and country is whiter than ever. "It just amazes me,'' Downing says. "And it's the industry that's doing it, it's not the people. I went down to Warner Brothers when they had a coming out party for this 'From Where I Stand,' and they had two or three black groups and a couple of black country singers on there and they were fabulous. One of them got signed to Arista, and now I heard that they dropped them even before they released the record. It seems like they don't want to take a chance on ruffling the waters. But it's the industry, not the people, 'cause everywhere I go I'm playing for country fans and I get standing ovations.''

Downing adds that, in the current market, being black is only part of the problem. "These days, they're going to that young thing -- if you're over 24, get back. It used to be 'If you're black, get back,' but now it's if you're over 24. George Jones and Waylon Jennings and all of these people that make good country music can't be heard anymore, and I think that's wrong.''

Nonetheless, Downing seems anything but discouraged. As he finishes the interview, he starts putting on tapes of new songs, including a novelty number in the current, rock-tinged country style about catching a catfish who sings like Elvis. After the Johnny D's gig, he's off to Europe on a tour with Brenda Lee, and he's looking for a label for his new album. "I think there is a market for my music out there,'' he says brightly. "I really believe that, and I'm not gonna let them get me down. I'm gonna keep trying and keep kicking until the good lord puts me in the grave -- and even then I might come back and start kicking some more.''

Back to the Archive Contents page

By Elijah Wald

Globe Correspondent

On the telephone, Doc Watson sounds just about the same he does on record or on stage. His voice is plain and unassuming. He answers questions politely but laconically, without any frills or digressions.

Watson is something of an anomaly: On the one hand, he is a traditional, unvarnished folk singer and guitarist from rural Appalachia. On the other, he learned most of his repertoire from records and is a musical innovator whose work forever changed his instrument. Having got his professional start playing electric guitar in a rockabilly band, he has gone on to be among the most resolutely old-fashioned performers to come out of the 1960s urban folk boom.

"I never forsake the roots,'' he says, speaking from his North Carolina, home. "I grew up with that here in the mountains. I'm a country boy, a hillbilly if ever there was one. So I always go back and get some of that, and the audiences demand that, in a way. They want to hear the same mixture that I've always done.''

Nonetheless, Watson has over the years shown surprising range. He has recorded blues, bluegrass and contemporary folk albums. His next-to-last disc was a rockabilly excursion that had him singing 1950s hits and trading licks with Duane Eddy. His latest, "Doc & Dawg'' (Acoustic Disc), a duet set with David Grisman, has him attacking numbers like "Summertime'' and "Sweet Georgia Brown'' along with old fiddle tunes, ballads, and sentimental numbers.

Recently, Watson has been playing a bit more jazz and rock ("Let's call it rockabilly; I never did do any hard rock,'' he corrects), and he clearly enjoys the change. The jazz tunes, in particular, give him a chance to stretch out on guitar, and his playing can be startling to those who only know his fiddle-tune adaptations.

"Well, it's country-style jazz,'' he says, a bit self-deprecatingly. "It's not with all the accidentals and all that stuff. And I can't imagine ever going fully in that direction. I love the traditional music enough to stick by it. I've been asked, 'How do you classify your music?' Well, I classify it as 'traditional plus,' and that's about what it comes to.''

That description would cover what he was doing even at his most pure and old-fashioned. Watson's first recordings, while exclusively of old-time songs, created a revolution in guitar playing. Before him, bluegrass guitarists were strictly rhythm players. When he picked "Black Mountain Rag'' on his first album, the role of the instrument was transformed.

Not that Watson will take all the credit. "Somebody else was getting a handle on that at the time I started learning fiddle tunes on the guitar,'' he says firmly. "Hank Garland, who later became a jazz guitar player, in the beginning he played a bunch of fine music with Red Foley, and there was also Grady Martin who was a great lead guitar player, and they didn't hear Doc Watson in the beginning. They were doing their own thing.

"Myself, I just decided because I never could seem to master the fiddle that I wanted to play some fiddle tunes on the guitar. I started doing that in the '50s on the electric guitar for people to square dance to when we didn't have a fiddle. And then when I got caught up in the folk revival in the early '60s, I decided to do some of those things on the stage as part of my program.''

Despite his influence on later Nashville players, and his status as a country icon, Watson says that he was never approached by the c&w mainstream. "I never got any offers from Nashville. Until the folk revival came along there was no place for a handicapped person on the stage. You had to do a flashy show, and I'm afraid I wasn't part of that scene. Then, with the folk revival, all at once the thing changed. There was a place for people who played music for entertainment and not flash for show.''

Looking back, Watson is just as happy that Nashville never called. "Stardom never interested me. To me, that's not part of the game. I feel like I developed whatever talent the good Lord gave me when I come here for a reason, and my reason was to entertain people and give people some pleasure and to earn a living -- and earning a living was just about on the same line as enjoying it and playing for people's enjoyment. To me that's what it was about, and I never had any delusions of grandeur: "Hey, look who I am," and all the foolishness. To me that's not necessary. I'm afraid that I'm one of these fellows that don't want to get on the pedestal.''

Despite such protestations, by now Watson is accorded a respect in the country field that is matched by very few other performers, though he is typically modest in his assessment of it: "You know, the reputation, if you do a thing well, it happens. It's not something that you do on purpose. If you really enjoy entertaining people and enjoy what you do, that will just happen.''

These days, Watson plays only about 25 concerts a year, but he says that at 74 his enjoyment of performing is undiminished. "I hate the road, I never have enjoyed it. I like to be at home. But you never get tired of entertaining folks. It's always interesting, and somehow they pull about the best you have out of you. If I said I was tired of a good audience, that'd be a barefaced lie.''

Back to the Archive Contents page

By Elijah Wald

Globe Correspondent

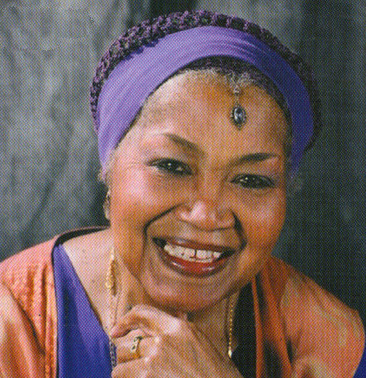

It has been quite a year for Odetta. In September, she recieved

the National Medal of Arts. Her new album, "Blues Everywhere

I Go" (MC Records), was nominated for a Grammy and two W.C.

Handy Awards. And she is touring more than she has in years.

It has been quite a year for Odetta. In September, she recieved

the National Medal of Arts. Her new album, "Blues Everywhere

I Go" (MC Records), was nominated for a Grammy and two W.C.

Handy Awards. And she is touring more than she has in years.

So what does she think about all of this? First off, she says on the phone from a tour stop, she is greatly relieved that she did not win the Grammy. Why? "Everybody else in that traditional blues category has been doing blues since before God made dirt," she laughs. "So for this young wippersnapper to come up and make a blues record and win would not be kosher."

The aforementioned wippersnapper will turn 70 this December and has been a professional musician for roughly 50 years. Though better known as a folksinger, she recorded a fine blues album in 1962 backed by first-rate jazz players. Still, the new disc is indeed something new for her. It has Jimmy Vivino on electric guitar and Dr. John guesting on piano and singing a duet of "Please Send Me Someone to Love," and the arrangements are an adept blend of old and new. As for her vocals, they sound less influenced by the classic blues queens of the 1920s, and more like Odetta just kicking back and being herself.

Odetta says that much of her understanding of how to sing blues came from watching the legendary Alberta Hunter’s comeback in the 1970s: "The younger [singers], when we heard the blues records we heard energy, and I thought the way you got the energy was to yell, holler and scream. And as I watched that little lady she didn’t yell, holler or scream one time. She just focused on the story she was telling. I’m continuing to learn from her, it is the greatest classroom I’ve ever been in."

On the new album, Odetta has carefully selected songs with messages, many of them obscure numbers found for her by Bessie Smith’s biographer, Chris Albertson. She sings Smith’s "Rich Man Blues" and "Homeless Blues," Victoria Spivey’s "T.B. Blues," and the "Unemployment Blues." In her interpretation, these pieces sound neither old nor new, but ageless, and they are quite unlike the stomping, raucous material that fills so many contemporary blues sets.

"So much of the blues that you hear carry out the stereotypes, in as far as we as blacks in this country are concerned," Odetta says seriously. "When the young [white] guys were going around collecting blues, they were interested in the double entendre and the purient, the blues that helped support what white people thought about black people -- and that was ‘I’m gonna cut you, I’m gonna shoot you, and you did me wrong.’

"I’m not saying that those things were not within the blues area, because they could not have collected them if they weren’t there. But I would like to know what other songs they left out of their collections, like the blues that were talking about the hardness of life, the hard times that people had to go through, and other parts of our lives outside of the sex and the killing and maiming."

When she talks about these issues, Odetta sounds like the figure long known to folk fans, who uses traditional music to get to the heart of contemporary concerns. The new album, though, displays another Odetta as well. For the first time in her life, she sounds cheerfully, exuberantly sexy, audibly licking her lips over the lyric of Sippie Wallace’s bawdy "You Gotta Know How," which closes the album.

"Isn’t that a devilish song?" she asks happily. "I just love to do that. People just giggle. And I think for a lot of people who know of what my work is so far, that’s just the other pole of whatever it is that they have witnessed from me."

This other side will be on display at Passim, where she will do half the show singing folksongs to her own guitar, but the other half accompanied by pianist Seth Farber and singing blues. "With the guitar, the folk music, maybe because of how I was when I first started in folk music, I’m so deadly serious," she says. "Sometimes I disgust myself with the seriousness, there are times I say, ‘’Detta, come on, please.’

"I guess it’s because when I came into folk music I was a scared kid, and I was also working off a lot of hate and anger. Well, the music has healed an awful lot of that, so that when it comes to today I’m a whole other person. So you bring to what you do, what you are. Your approach to it changes, and it is possible for me to have fun with the music now. It is even possible for me to laugh. Within the blues, I can play."

Back to the Archive Contents page

By Elijah Wald

Globe Correspondent

The Klezmatics, who come to Somerville Theatre this Sunday, are probably the leading band in the revival of klezmer music, the Eastern European/Jewish/Pop/Jazz fusion music that was relegated to weddings and bar mitzvah’s until staging a surprising comeback in the 1980s. And revival is the right word, because the Klezmatics are trying to make the music live again, not just to exhibit its vanished glories.

"I was not around [in the golden age of the 1920s and 1930s], and it’s hard to be nostalgic about things I never experienced," says Lorin Sklamberg, the band’s piano and accordion player and lead vocalist. "In the very beginning our thing was to try and learn the music, and the models were old recordings that reflect a certain place and time. But once we got the language and became facile at the inflections and the ornamentation, then you can go off on your own. And, for me, the music that’s the most authentic is music that reflects the personality of the performer. So, in that sense I think of our band as being very authentic."

For one thing, that means that the Klezmatics’s lyrics cover subjects that are by no means typical for the genre. Sklamberg is gay, and addresses all romantic songs to a male love interest, as well as tossing a line into one song saying "We’re all gay, like Jonathan and King David." Then, the band’s 1996 "Possessed" album (Xenophile) has a cleverly written ode to the pleasures of marijuana, though non-Yiddish speakers would not know unless they read the liner notes.

Of course, non-Yiddish speakers represent the majority of the band’s audience. While most of the flood of Eastern European immigrants to the U.S. spoke the language, it fell out of favor after World War II, and even Sklamberg himself only learned to speak it after he began working as a klezmer singer: "I grew up in a suburban Los Angeles conservative Jewish community, learning Hebrew like everyone else" he says. "Because of the Holocaust, speaking Yiddish was not looked upon as the healthy thing to do. Basically it was like a gung-ho, rah-rah Israeli culture thing, and I kind of feel like I was deprived of my heritage. Of course, now I have gotten it back with a vengeance, but I had to move to New York to do it."

As in the songs, Sklamberg does not mince words in interviews, and one might expect that the older, more conservative Jewish audience would have a problem with that. According to Sklamberg, however, the band has received few negative reactions. "We have always expressed a kind of a radical political outlook," he says. "But I think that if you do something with conviction, that if anyone comes with any sort of prejudice they end up leaving it at the door. That's been our experience, anyway. Actually, I think that a lot of the time audiences are puzzled less by our politics than by some of the musical vocabulary. People like [horn players] Frank [London] and Matt [Darriau] come from a jazz background so they bring things to our shows that might not be within the realm of understanding of some of the people that come to the concerts."

Meanwhile, the Klezmatics’ audience has moved far beyond the normal klezmer crowd, in part due to the band’s eclectic assemblage of collaborators. They have recorded with Itzak Perlman, Allen Ginsberg, the Moroccan Master Musicians of Jajouka, and the Israeli singer Chava Alberstein, scored playwright Tony Kushner’s adaptation of "The Dybbuk," and are currently preparing a tour with the avante-garde Pilobolus Dance Theatre. London is also music director for "The Memoirs of Gluckel of Hameln," an experimental puppet-and-theater performance which is in town this weekend at the Jewish Theatre of New England. (He will play at the Saturday evening and Sunday matinee performances, with a substitute on Sunday evening. Information: 617-965-5226.)

Sklamberg says that this breadth of work was by no means something that the musicians expected when they started playing klezmer. "We started the band to play parties and make a little extra money," he says. "It never occurred to us until later that we would go in this kind of direction, and actually it wasn’t even our idea." The impulse came largely from a label owner in Berlin who encouraged them to be more musically adventurous, to reshape the music to their own time and tastes.

Even today, Sklamberg says that the band’s audiences are far more varied in Europe. In the United States, with the exception of New York, audiences remain largely Jewish, something that is in one sense disappointing, but hardly unexpected. "It’s still Jewish music," Sklamberg says. "We do hybrids of other kinds of stuff, but it’s still a Yiddish band. I know other klezmer bands that don’t use the word ‘Jewish’ anywhere in their press material, and I don’t know what that’s about. I like that it’s Jewish music, and I like what we do."

After all, the musicians are Jewish, so it is as natural for them to play Jewish music as for a Puerto Rican musician to play salsa, or a white Tennesseean to sing country. Just as it is natural for them to keep changing the music to fit their own experience. "We ended up really putting ourselves into the music, and expressing our musical personalities," Sklamberg says. "At this point our music is really associated with the players, people expect to see me and [violinist] Alicia [Svigals] and Frank and Matt, and our personalities affect the way the music is played. And I think that that is really a good thing."