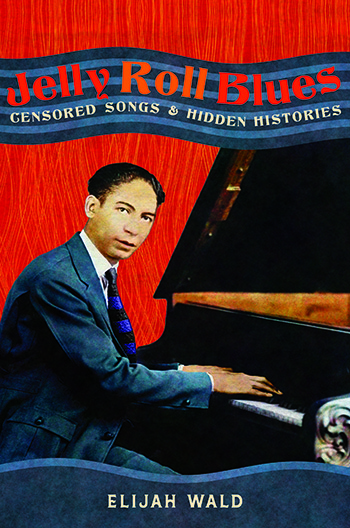

Elijah Wald – Jelly Roll Blues

[Home] [Bio] [Jelly Roll Blues] [Robert Johnson] [Dave Van Ronk] [Narcocorrido] [Dylan Goes Electric] [Beatles/Pop book] [The Dozens] [Josh White] [The Blues] [Hitchhiking] [Other writing] [Musical projects] [Joseph Spence]

Jelly Roll Blues: Censored Songs and Hidden Histories (Hachette 2024). Please buy from your local bookstore or through Bookshop.org, which credits local bookstores.

Jelly Roll Blues: Censored Songs and Hidden Histories (Hachette 2024). Please buy from your local bookstore or through Bookshop.org, which credits local bookstores.

Jump to description of book chapters

Errata (post-publication corrections or emendations)

"Wald evokes a world of barrelhouse piano and honky-tonks that would make the denizens of a Weimar cabaret blush…Along the way, he astutely analyzes the intermingling of ethnicity, gender, and social class that shaped popular music… An illuminating, deeply researched study of roots music, decidedly not suitable for work.”

—Kirkus, *starred review*

"One of the most illuminating music writers working today… Wald seeks not only to reconstruct a little-known body of music, but to explore and reveal the social world out of which that music came…. “Jelly Roll Blues” enriches our sense of how the world used to sound… and should appeal to any readers who want to deepen their knowledge of the foundations of American music…. truly virtuosic."

—Steve Waksman, The Boston Globe

"...magnificent, raunchy exploration of early blues.... If I had to pluck one word from this book that represents it best, it would be 'funk,' a word Mr. Wald uses repeatedly.... Most mainstream art is proper. But if the blues were proper, it wouldn’t be the blues."

—David Kirby, The Wall Street Journal

Jelly Roll Blues is a journey through the censored voices of early blues and jazz, and the deep culture of the Black sporting world, guided by the songs and memories of Jelly Roll Morton.

Morton became famous in the 1920s as a composer and bandleader, but got his start as a singer and pianist entertaining customers in the honky-tonks and bordellos of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast. He recorded an oral history of that time in 1938 for the Library of Congress, but the most distinctive songs were hidden for over fifty years, because the language and themes were as wild and raunchy as anything in gangsta rap.

Those songs inspired me to explore how much other history was locked away and censored in the early years of the twentieth century, and this book is the result. Full of previously unpublished lyrics and stories, it provides an alternate view of the dawn of American popular music, when jazz and blues were still the private, after-hours music of the Black sporting world, and in particular of the women who were that world's most celebrated figures. It gives new insight into familiar figures like Buddy Bolden and Louis Armstrong, and introduces characters like Ready Money, the New Orleans sex worker and pickpocket who ended up owning one of the largest Black hotels on the West Coast. It is a journey to a fascinating period when a new generation of Black musicians, dancers, and listeners were shaping lives their parents could not have imagined and art that transformed popular culture around the world.

Available from all better bookstores, or online from Bookshop.org.

“I grew up on the old blues: heard it, felt it, danced to it, but a lot of people didn’t hear the real stuff, because somebody else was controlling the narrative. This book is searching out those voices, keeping them from being lost, and helping to transfer that ancestral information to a new generation.”

--Taj Mahal

"Elijah Wald has done it again. Both a compelling study of blues pioneer and musical genius Jelly Roll Morton's roots and song craft as well as a meticulously-researched history of early twentieth-century, ostensibly “taboo” popular music culture, Jelly Roll Blues offers a clear-eyed exploration of Black modernist era vernacular music, and takes seriously graphic forms of cultural expression as articulations of human desire and as complex manifestations of social and economic lifeworlds shaped by racial and gender pressures and inequalities. Wald continues to challenge and expand what we know as well as what we think we know about the early blues."

--Daphne Brooks, professor of African American Studies; Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies; and Music at Yale University and author of Liner Notes for the Revolution: The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound.

"This book is riveting. Elijah Wald brings the world of the New Orleans demi-monde to raucous life through his excavation of the censored lyrics of early jazz and blues. Moreover, in showing how women participated in this musical culture—as musicians in their own right, audience participants, and prostitutes enjoying some leisure time after hours—he reveals a world scarcely glimpsed before and all but erased from history. What Wald recovers here borders on the miraculous."

--Emily Landau, author of Spectacular Wickedness: Sex, Race, and Memory in Storyville, New Orleans

"Wald’s book is a fascinating exploration of the lyrics, dances and performances of early 20th century Black Americans, much of which has been buried in libraries and archives. He masterfully connects jazz to contemporary popular music, relates the struggles of Black performers, examines the changing standards for censoring popular culture, and adds to the epic that was Jelly Roll Morton’s life. Essential reading."

--John Szwed, author of Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World and historical notes for Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings.

"Elijah Wald is one of our most skilled and affable guides to the hidden, governing currents within the long stream of American music, and with Jelly Roll Blues he navigates one of the most important: the erotic, provocative and just plain dirty songs at the heart of jazz and blues. This book travels into the heart of the sporting life, vividly recounting a time when working women and dandyish men invented a musical language that not only celebrated life's greatest pleasures but told truths that other art forms were too tame to touch. A hot and essential read."

--Ann Powers, NPR music critic and author of Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black & White, Body and Soul in American Music

"Elijah Wald’s latest excavation of American popular culture reminds us that music is meant to reflect life as it is, despite the genteel aspirations of commercial window-dressers. Jelly Roll Blues gives by far the most realistic and satisfying account of Morton’s cultural environment to date, while also revealing the importance of cultural networks that operated beneath the commercial mainstream. Highly recommended."

--Bruce Boyd Raeburn, curator emeritus, Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and Jazz, Tulane University

"Elijah Wald’s incisive, deeply researched, and hugely entertaining new book reminds us of the power of stories and storytelling to both shape and illuminate worlds, and what is lost when those narratives are disrupted. Using Jelly Roll Morton’s fascinating 1938 Library of Congress musical memoir as a jumping off point, and through his careful engagement with previously censored lyrics and obscured lives, Wald invites us on an important journey toward correcting incomplete historical accounts of early blues and jazz."

--Kimberly Mack, associate professor of English at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and author of Fictional Blues: Narrative Self-Invention from Bessie Smith to Jack White

"I enjoyed Jelly Roll Blues immensely. Whatever one’s estimate of Morton’s importance and credibility, there is no doubt about his ability to be in interesting places at interesting times, doing interesting things. Wald guides the reader round that world with admirable clarity. For blues scholars and enthusiasts, some of his observations about the history and origins of the form will be required reading.”

--Tony Russell, author of The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray and Rural Rhythm.

"We had plenty of fun, the kind of a fun I don't think I've ever seen any other place. Of course, there may be nicer fun, but that particular kind -- there was never that kind of fun anyplace, I think, on the face of the globe but New Orleans."

--Jelly Roll Morton, Library of Congress Recordings

What's in the Book:

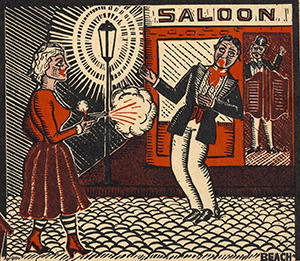

Introduction: Songs and Silences explores what people were singing in saloons, on farms, on ships, and on the Western prairies before the arrival of mass media... and how those songs were censored and rewritten by folklorists, commercial publishers, and record producers. By looking at what people actually sang, we get a deeper sense of their lives and viewpoints, and find unexpected connections, like a popular sailors' shanty that was considered "unprintable" and has never before been published in uncensored form -- but is first mentioned in Twelve Years a Slave and resurfaced in cowboy songs, fiddle tunes, a vicious satire of Reconstruction, and blues.

Introduction: Songs and Silences explores what people were singing in saloons, on farms, on ships, and on the Western prairies before the arrival of mass media... and how those songs were censored and rewritten by folklorists, commercial publishers, and record producers. By looking at what people actually sang, we get a deeper sense of their lives and viewpoints, and find unexpected connections, like a popular sailors' shanty that was considered "unprintable" and has never before been published in uncensored form -- but is first mentioned in Twelve Years a Slave and resurfaced in cowboy songs, fiddle tunes, a vicious satire of Reconstruction, and blues.

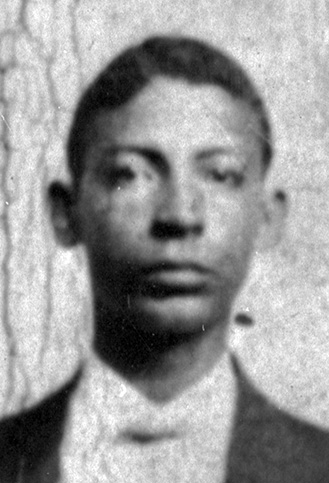

Chapter 1: Alabama Bound follows the young Ferdinand "Winding Ball" Morton from the neighborhoods of New Orleans, along the Gulf Coast, up to Beale Street in Memphis, and west, playing "every pig pen from Orange to El Paso." In the decades after the Civil War, Black Americans were asserting new freedoms by changing their places, their names, and their worlds, and Morton's journey was both unique and typical. He was singing raw blues and sentimental ballads, playing ragtime dance music, and learning from everyone from rough honky tonk players like Brocky Johnny to his early idol, the gay piano master Tony Jackson, whose "range on a blues tune would be just exactly like a blues singer; on an opera tune would be just exactly as an opera singer."

Chapter 1: Alabama Bound follows the young Ferdinand "Winding Ball" Morton from the neighborhoods of New Orleans, along the Gulf Coast, up to Beale Street in Memphis, and west, playing "every pig pen from Orange to El Paso." In the decades after the Civil War, Black Americans were asserting new freedoms by changing their places, their names, and their worlds, and Morton's journey was both unique and typical. He was singing raw blues and sentimental ballads, playing ragtime dance music, and learning from everyone from rough honky tonk players like Brocky Johnny to his early idol, the gay piano master Tony Jackson, whose "range on a blues tune would be just exactly like a blues singer; on an opera tune would be just exactly as an opera singer."

Chapter 2: Hesitation Blues takes its title from the most popular blues song of the 1910s, sung in juke joints, colleges, dance halls, bordellos, and the backrooms of every saloon. Morton sang it at the Library of Congress, but hesitated when he came to a favorite stanza, explaining, “This is a dirty little verse -- couldn't say that." Many singers were hesitant about performing their usual verses for outsiders, and widespread favorites like "Uncle Bud" and "Stavin' Chain" were forgotten or buried in archives. Fortunately, some uncensored versions survived, thanks to singers like Mance Lipscomb and Gary Davis, and scholars like Zora Neale Hurston.

Chapter 2: Hesitation Blues takes its title from the most popular blues song of the 1910s, sung in juke joints, colleges, dance halls, bordellos, and the backrooms of every saloon. Morton sang it at the Library of Congress, but hesitated when he came to a favorite stanza, explaining, “This is a dirty little verse -- couldn't say that." Many singers were hesitant about performing their usual verses for outsiders, and widespread favorites like "Uncle Bud" and "Stavin' Chain" were forgotten or buried in archives. Fortunately, some uncensored versions survived, thanks to singers like Mance Lipscomb and Gary Davis, and scholars like Zora Neale Hurston.

Chapter 3: Winding Ball takes its title from Morton's original nickname, before he graduated from honky-tonks to theaters and became Jelly Roll. It was also the title of his theme song, which he recorded for the first time at the Library and later censored for commercial discs -- and which sparked a bitter dispute with W.C. Handy, whose claim to be "The Father of the Blues" was matched by Morton's claim to be the inventor of jazz. The phrase had a long and convoluted history, reaching back to the Scottish bawdry of Robert Burns, and paralleled the journey of the "Derby Ram," which traveled from Britain, was embraced by George Washington, ragged by James Weldon Johnson, and became the most popular jazz funeral march.

Chapter 3: Winding Ball takes its title from Morton's original nickname, before he graduated from honky-tonks to theaters and became Jelly Roll. It was also the title of his theme song, which he recorded for the first time at the Library and later censored for commercial discs -- and which sparked a bitter dispute with W.C. Handy, whose claim to be "The Father of the Blues" was matched by Morton's claim to be the inventor of jazz. The phrase had a long and convoluted history, reaching back to the Scottish bawdry of Robert Burns, and paralleled the journey of the "Derby Ram," which traveled from Britain, was embraced by George Washington, ragged by James Weldon Johnson, and became the most popular jazz funeral march.

Chapter 4: Buddy Bolden's Blues touches on another legendary inventor of jazz, the powerhouse trumpeter Buddy Bolden; explores the evolution of brass band blues; and celebrates forgotten figures like George "The Rhymer" Jones, whose lyrical improvisations--a precursor of modern rap freestyling--made him one of the most popular entertainers in the red light district. Old-timers recalled that Morton "did rhyming like George, except Jelly put more music to it." Morton made the first recording of Bolden's theme song, "Funky Butt," and takes us back to the roots of funk -- crowded rooms of heated bodies in an era before most people had bathtubs -- with a side trip to Kid Ory's challenge song, which gave new meaning to an old Mardi Gras Indian chant called "Chock-a-Mo" or "Iko Iko."

Chapter 4: Buddy Bolden's Blues touches on another legendary inventor of jazz, the powerhouse trumpeter Buddy Bolden; explores the evolution of brass band blues; and celebrates forgotten figures like George "The Rhymer" Jones, whose lyrical improvisations--a precursor of modern rap freestyling--made him one of the most popular entertainers in the red light district. Old-timers recalled that Morton "did rhyming like George, except Jelly put more music to it." Morton made the first recording of Bolden's theme song, "Funky Butt," and takes us back to the roots of funk -- crowded rooms of heated bodies in an era before most people had bathtubs -- with a side trip to Kid Ory's challenge song, which gave new meaning to an old Mardi Gras Indian chant called "Chock-a-Mo" or "Iko Iko."

Chapter 5: Mamie's Blues is named for Mamie Desdunes, the pianist whom Morton recalled as singing "the first blues I no doubt heard in my life." It was about the hard life of a New Orleans streetwalker, and this chapter explores the lives and culture of the women who worked the "tenderloin" entertainment districts in the decades before the First World War, including forgotten figures like Miss Ready Money, who went from picking pockets to owning a grand hotel and nightclub, and revisits the songs of their world, from straightforward lyrics of sex as nightly labor to the classic "Shave 'Em Dry." Early jazz artists recalled those women as the core audience for blues, and their tastes and viewpoints were fundamental in shaping the new style.

Chapter 5: Mamie's Blues is named for Mamie Desdunes, the pianist whom Morton recalled as singing "the first blues I no doubt heard in my life." It was about the hard life of a New Orleans streetwalker, and this chapter explores the lives and culture of the women who worked the "tenderloin" entertainment districts in the decades before the First World War, including forgotten figures like Miss Ready Money, who went from picking pockets to owning a grand hotel and nightclub, and revisits the songs of their world, from straightforward lyrics of sex as nightly labor to the classic "Shave 'Em Dry." Early jazz artists recalled those women as the core audience for blues, and their tastes and viewpoints were fundamental in shaping the new style.

Chapter 6: Pallet on the Floor starts with a song known throughout the South, which Morton expanded into a explicit epic of a sporting man seducing a working man's wife. There is nothing else like it on record, because pornography laws and early recording technology would have made any recording impossible. This chapter explores the oral culture that was lost or obscured through prudery and censorship... and what remains, including a formidable collection of uncensored, unpublished material from William McKinney, a young Black researcher in New Orleans. Blues singers documented and celebrated behaviors and lifestyles that were ignored and disparaged in mainstream media, including gay and lesbian worlds that were far more open and public than most histories suggest.

Chapter 6: Pallet on the Floor starts with a song known throughout the South, which Morton expanded into a explicit epic of a sporting man seducing a working man's wife. There is nothing else like it on record, because pornography laws and early recording technology would have made any recording impossible. This chapter explores the oral culture that was lost or obscured through prudery and censorship... and what remains, including a formidable collection of uncensored, unpublished material from William McKinney, a young Black researcher in New Orleans. Blues singers documented and celebrated behaviors and lifestyles that were ignored and disparaged in mainstream media, including gay and lesbian worlds that were far more open and public than most histories suggest.

Chapter 7: The Murder Ballad

brings the story full circle, to the song that inspired this book: Morton's half-hour-long, 59-verse ballad about a sporting woman who kills a romantic rival, goes to jail, forms a lesbian relationship, and eventually dies with a classic warning to other women. By far the longest blues ballad, it was buried for more than fifty years because the heroine uses the raw words common in streets and saloons rather than the bowdlerized language of middle-class media. Going back to the 1890s, we explore a golden age of Black sporting ballads, from "The Bully," which started the ragtime song craze and was traced to a Black bordello in St. Louis, to "Stackolee," "Duncan and Brady," "Frankie and Albert [or Johnny]," and the New Orleans sagas of "Ella Speed" and the "House of the Rising Sun." These songs formed a bedrock for artists like the legendary Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter and Sullivan Rock, the New Orleans pianist who inspired Professor Longhair -- and for folklorists like the Lomaxes, who preserved Black traditions but also reshaped, redefined, and sometimes obscured them.

Chapter 7: The Murder Ballad

brings the story full circle, to the song that inspired this book: Morton's half-hour-long, 59-verse ballad about a sporting woman who kills a romantic rival, goes to jail, forms a lesbian relationship, and eventually dies with a classic warning to other women. By far the longest blues ballad, it was buried for more than fifty years because the heroine uses the raw words common in streets and saloons rather than the bowdlerized language of middle-class media. Going back to the 1890s, we explore a golden age of Black sporting ballads, from "The Bully," which started the ragtime song craze and was traced to a Black bordello in St. Louis, to "Stackolee," "Duncan and Brady," "Frankie and Albert [or Johnny]," and the New Orleans sagas of "Ella Speed" and the "House of the Rising Sun." These songs formed a bedrock for artists like the legendary Huddie "Lead Belly" Ledbetter and Sullivan Rock, the New Orleans pianist who inspired Professor Longhair -- and for folklorists like the Lomaxes, who preserved Black traditions but also reshaped, redefined, and sometimes obscured them.